Is eutopia the default outcome post-AGI?

In the new paper “No Easy Eutopia”, we argue that reaching a truly great future will be very hard.

How easy is it to get to a future that’s pretty close to ideal?

You could think of reaching eutopia as like an expedition to sail to an uninhabited island. The expedition is more likely to reach the island to the extent that:

The island is bigger, more visible, and closer to the point of departure;

The ship’s navigation systems work well, and are aimed toward the island;

The ship’s crew can send out smaller reconnaissance boats, and not everyone onboard the ship needs to reach the island for the expedition to succeed.

Similarly, we could be on track for a near-best future for a few different reasons.

First, eutopian futures could present a big target: that is, society would end up reaching a near-best outcome across a wide variety of possible futures, even without deliberately and successfully honing in on a very specific conception of an extremely good future. We call this the easy eutopia view.

Second, even if the target is narrow, society might nonetheless hone in on that target — maybe because, first, society as a whole accurately converges onto the right moral view and is motivated to act on it, or, second, some people have the right view and compromise between them and the rest of society is sufficient to get us the rest of the way.

In No Easy Eutopia, we focus on the first of these. (The next essay, Convergence and Compromise, will focus on the next two.) We argue there are many ways in which future society could miss out on most value, or even end up dystopian - many of which are quite subtle. The “target” of a near-best future is very narrow: very unlikely to happen by default, without some beings in the future trying hard to figure out what’s best, and actively trying to make the world as good as possible, whatever “goodness” consists of.

You might think that it’s obvious that getting to eutopia is really hard. But we think this is not at all obvious. As we define quantities of value, we say that X future is twice as good as Y future just in case a 50–50 gamble between X and extinction in a few hundred years is as good as a guarantee of Y.

And now consider a “common-sense utopia”:

Common-sense utopia: Future society consists of a hundred billion people at any time, living on Earth or beyond if they choose, all wonderfully happy. They are free to do almost anything they want as long as they don’t harm others, and free from unnecessary suffering. People can choose from a diverse range of groups and cultures to associate with. Scientific understanding and technological progress move ahead, without endangering the world. Collaboration and bargaining replace war and conflict. Environmental destruction is stopped and reversed; Earth is an untrammelled natural paradise. There is minimal suffering among nonhuman animals and non-biological beings.

Suppose we could either get the common-sense utopia for sure, or a 10% chance of a truly best-case future and a 90% chance of extinction in a few hundred years. Our intuitive moral judgments, at least, are strongly in favour of taking the common-sense utopia.

But, ultimately, we think that intuitive moral judgment is mistaken. Here are two different arguments for that.

Future moral catastrophe

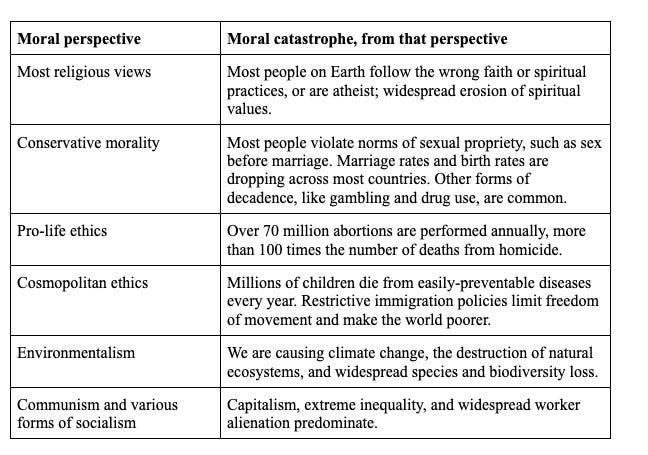

Today, we live in the midst of a moral catastrophe.

Technological and material abundance has given us the opportunity to create a truly flourishing world, and we have utterly squandered that opportunity.

Consider our impact on farmed animals alone: every year, tens of billions of factory-farmed animals live lives of misery. The suffering directly caused by animal farming may well be enough to outweigh most or all of the gains to human wellbeing we have seen. For this reason alone, the world today may be no better overall than it was centuries ago

Maybe you don’t care about animal welfare. But then just think about extreme poverty, inequality, war, consumerism, or global restriction on freedoms. These all mean that the world falls far short of how good it could be.

In fact, we think most moral perspectives should regard the world today as involving a catastrophic loss of value compared to what we could have created.

That’s today. But maybe the future will be very different? After superintelligence, we’ll have material and cognitive abundance, so everyone will be extremely rich and well-informed, and that’ll enable everyone to get most of what they want - and isn’t that enough?

We think not. We think there are many subtle ways in which the world could lose out on much of the value it could achieve.

Consider population ethics alone. Does an ideal future society have a small population with very high per-person wellbeing, or a very large population with lower per-person wellbeing? Do lives that have positive but low wellbeing make the world better, overall?

Population ethics is notoriously hard - in fact, there are “impossibility theorems” showing that no theory of population ethics can satisfy all of a number of obvious-seeming ethical axioms.

And different views will result in radically different visions of a near-best future. On the total view, the ideal future might involve vast numbers of beings each of comparatively lower welfare; a small population of high-welfare lives would miss out on almost all value. But on critical-level or variable-value views, the opposite could be true.

If future society gets its population ethics wrong (either because of misguided values, or because it just doesn’t care about population ethics either way), then it’s easy for it to lose out on almost all potential value.

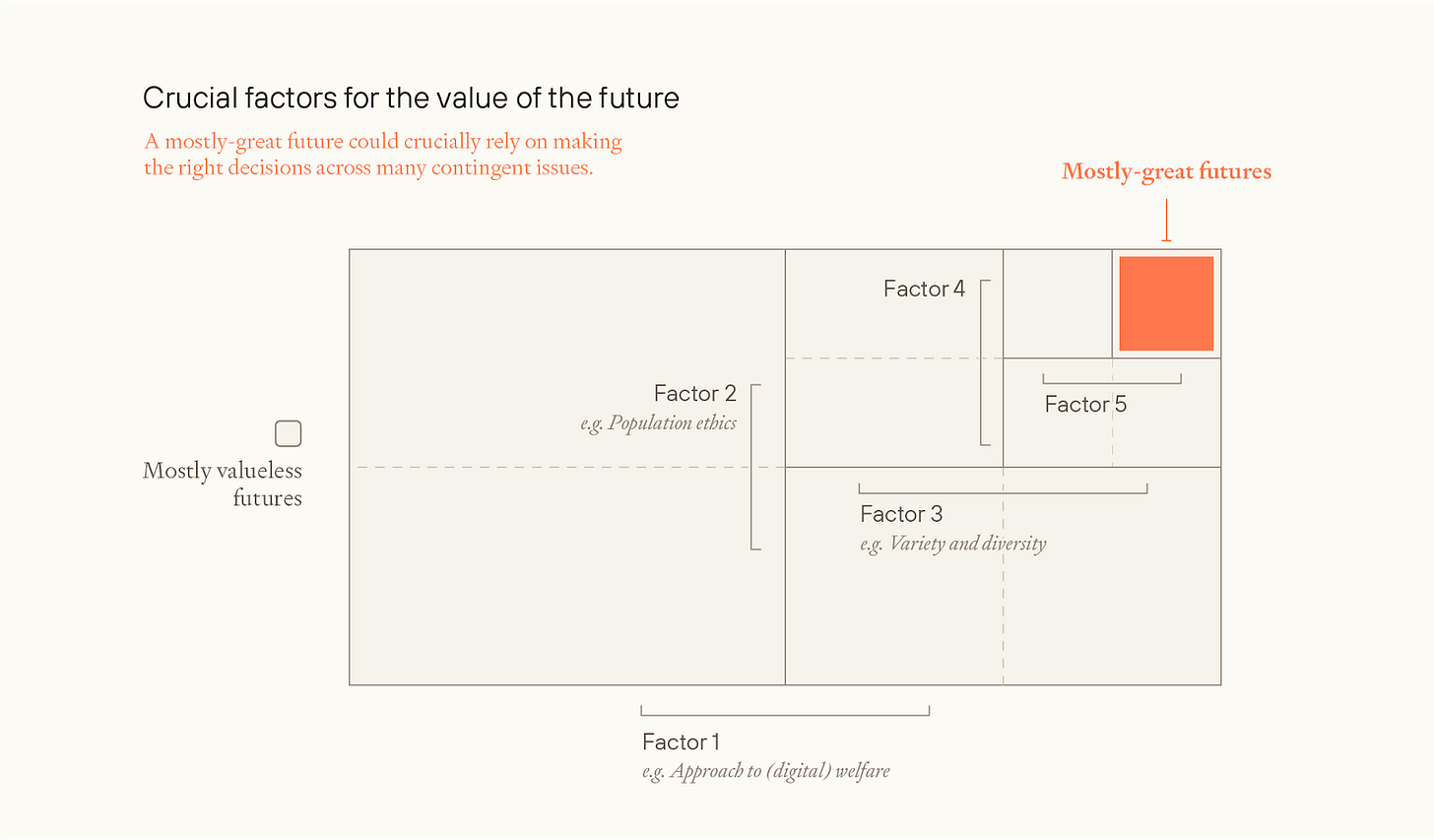

And that’s just one way in which society could mess things up. Consider, also, mistakes future people could make around:

Attitudes to digital beings

Attitudes to the nature of wellbeing

Allocation of space resources

Happiness/suffering tradeoffs

Banned goods

Similarity/diversity tradeoffs

Equality or inequality

Discount rates

Decision theory

Views on the simulation

Views on infinite value

Reflective processes

For most of these issues, there is no “safe” option, where a great outcome is guaranteed on most reasonable moral perspectives. Future decision-makers will need to get a lot of things right.

And it seems like getting just one of these wrong could be sufficient for losing much or most achievable value.

That is, we can represent the value as the product of many factors. If so, then a eutopian future needs to do very well on essentially every one of those factors; doing badly on any one of them is sufficient to lose out on most value.

How maximum achievable value varies with total resources

A different form of argument is more systematic.

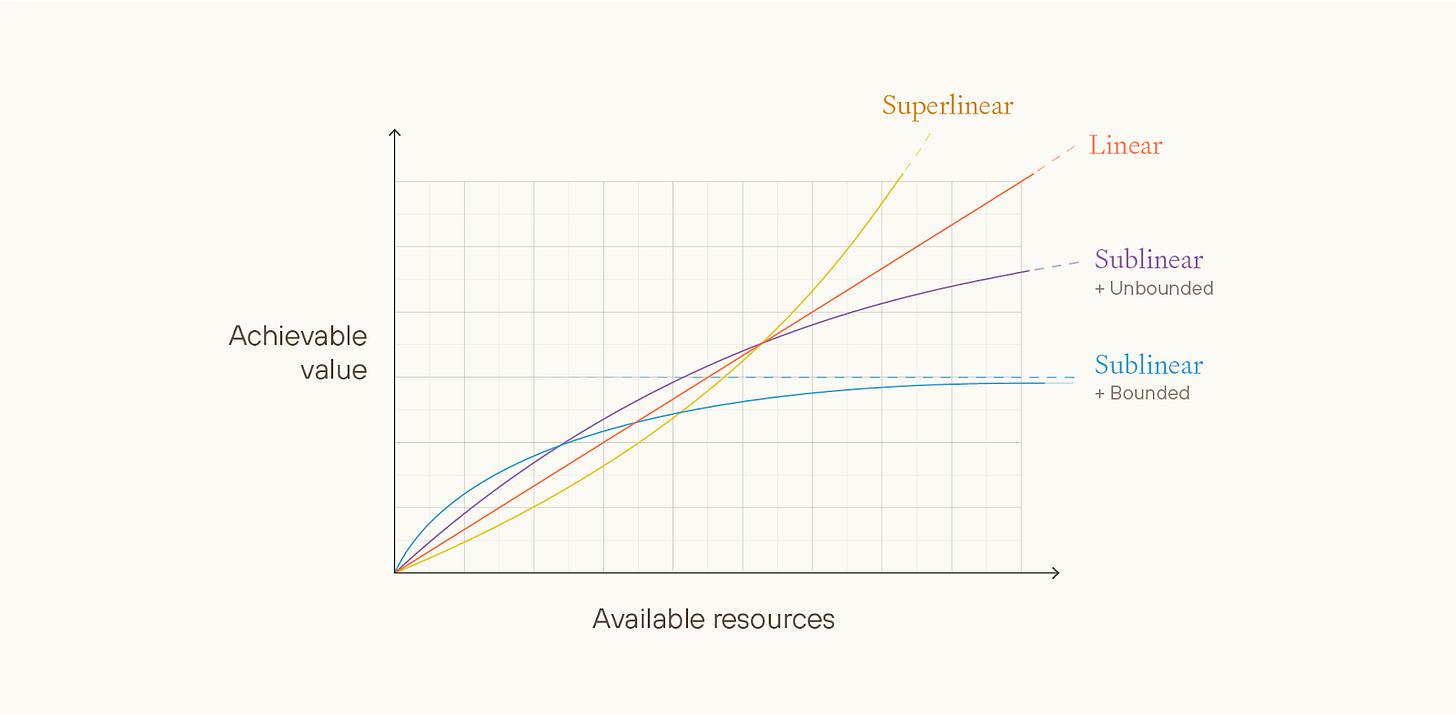

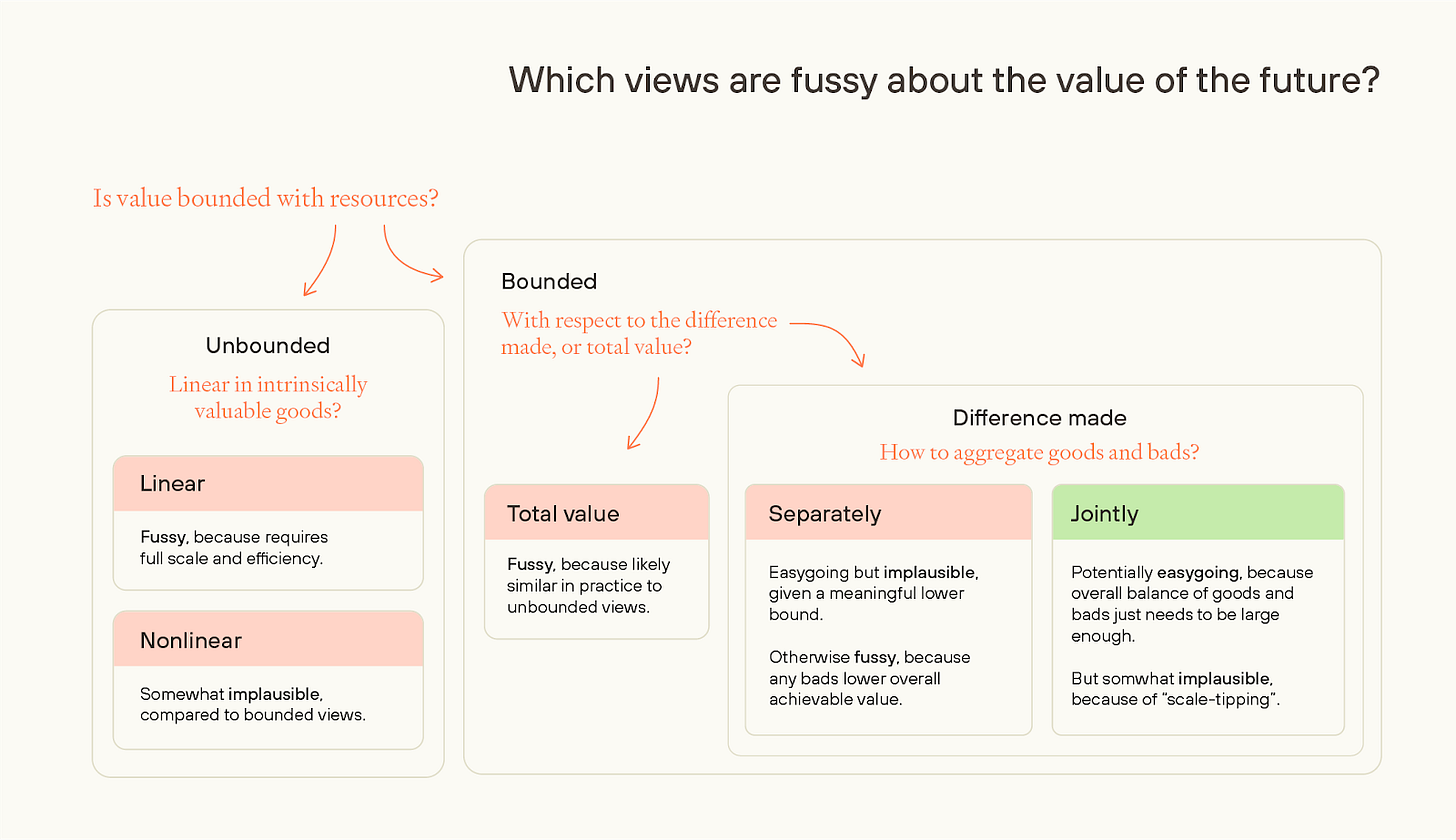

Some ways of valuing futures make it look comparatively easy to reach eutopia, because they regard a wide range of futures as close in value to the best feasible future. We’ll call these views easygoing. Other views make eutopia look comparatively hard; we’ll call these views fussy.

We can distinguish between different ethical views in terms of how much achievable value varies with total resources that could be used towards creating good outcomes, on these different views.

On unbounded ethical views, there’s no in-principle upper limit for maximum attainable value. Risk-neutral total utilitarianism is an example of an unbounded ethical view - any quantity of value is attainable as long as you have enough happy people.

Unbounded views could be approximately linear, superlinear, or sublinear with respect to the maximum achievable value that could be obtained with a given stock of resources.

Superlinear views seem very implausible and strictly fussier than linear views, and sublinear but unbounded views seem strictly less plausible and strictly fussier than sublinear and bounded views. So, in the essay, we don’t discuss either of them much.

Unbounded linear views are more plausible, but on such views, to reach a mostly-great future: (i) almost all available resources need to be used; and (ii) such resources must be put towards some very specific use.

E.g. on hedonistic total utilitarianism, almost all the accessible galaxies need to be used for whatever’s best. And, probably, the beings that experience joy most cost-effectively get a lot more joy per unit of resources than almost all other beings that could be created. This is a narrow target. More generally, the most plausible linear views are fussy.

Next, we can consider bounded views, meaning no possible world can exceed some fixed amount of positive value, even in theory.

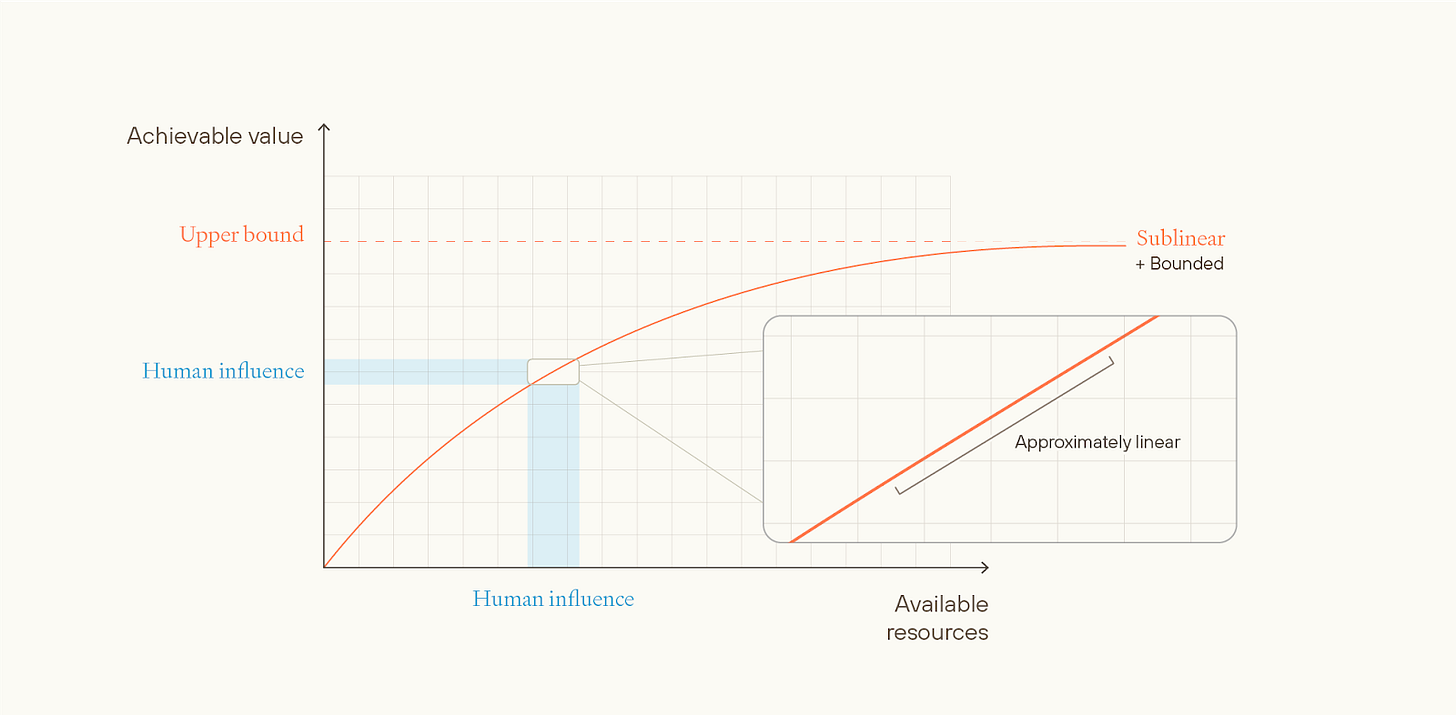

If a view is bounded with respect to the value of the universe as a whole, then it will be approximately linear in practice.

This is because the value of the universe as a whole is very large, and the difference that even all of humanity can make to that value is very small, and over small intervals, concave functions are approximately linear. And linear views are fussy.

In contrast, if the view is bounded with respect to the difference that humanity makes to the value of the universe as a whole, it might still be approximately linear in practice, if the bound is extremely high.

If the bound is “low” (as it would be if it matches our ethical intuitions), then future civilisation might be able to get close to the upper bound, even with a small quantity of resources.

But such views might still be fussy depending on how they aggregate goods and bads.

First, they could aggregate goods and bads separately, applying a bounded function to each of the amount of goods and amount of bads and then adding both. (I.e. the value of an outcome, v(o) = f(g) + h(b), where g and b are the quantities of goods and bads, respectively, and where f(.) and g(.) are bounded above).

But if so, then the value of the future becomes extremely sensitive to the frequency of bads in any future civilisation. Even if we weigh goods and bads equally (i.e. f(.) and g(.) are the same), then on a natural way of modeling we don’t reach a mostly-great future even if as little as one resource in 1022 is used toward bads rather than goods. So, such views are also fussy — requiring a future with essentially no bads at all.

Alternatively, you could aggregate jointly: i.e. you add up all goods and subtract the bads and then apply a bounded function to the whole. (v(o) = f(g – b)). If goods and bads are aggregated jointly, on a difference-making bounded view, then we plausibly have a view which is not fussy.

But this is quite a narrow slice of all possible views, and it suffers from some major problems that make it seem quite implausible. Some of the problems:

As noted, the value function has to concern the difference you (or humanity) make to the value of the universe. But such “difference-making” views have major problems, including that they violate stochastic dominance with respect to goodness. (These problems are described in more detail here.)

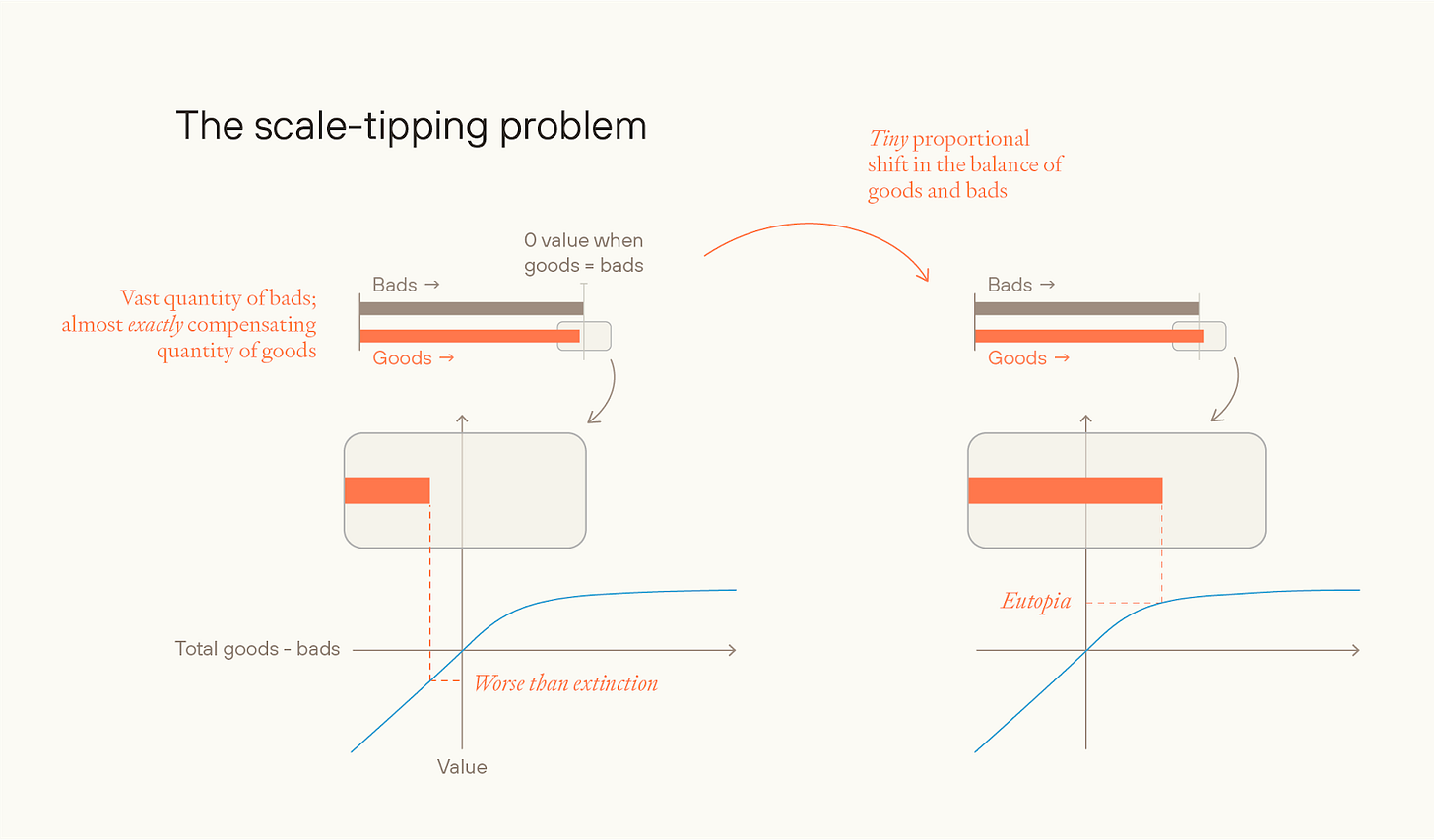

And separate aggregation seems at least as plausible as joint aggregation of goods and bads. Given joint aggregation of goods and bads, you have a “scale-tipping” problem, where a tiny change to the relative balance of goods and bads can move the value of the future from as-good-as- (or worse-than-) extinction, to eutopia.

Finally, any view that’s bounded above has to say implausible things about very bad futures, or else be strongly pro-extinction. If value is meaningfully bounded below, then in very bad worlds, the view will be willing to accept a very high likelihood of astronomical quantities of suffering in exchange for a small chance of a small amount of happiness.

If value is not meaningfully bounded below, then these views will generally become pro-human-extinction; the worst-case futures are much more bad than the best-case futures are good, so even a small chance of a very bad future can outweigh a much greater probability of even a near-best future.

Putting this all together, easygoingness about the value of the future seems unlikely to us.