Could one country outgrow the rest of the world?

Summary

Bostrom (2014) says that an actor has a “decisive strategic advantage” if it obtains “a level of technological and other advantages sufficient to enable it to achieve complete world domination”.

One obvious route to a decisive strategic advantage is military dominance.

This post explores a different route. Could the country that leads in AI outgrow the rest of the world economically? If so, they could get a decisive strategic advantage without acting aggressively towards other countries and without breaking any international norms.

I’ll focus here on the economic fundamentals, setting aside considerations like whether other countries would intervene militarily to prevent one country from pulling ahead.

I consider two arguments for why a country could outgrow the rest of the world.

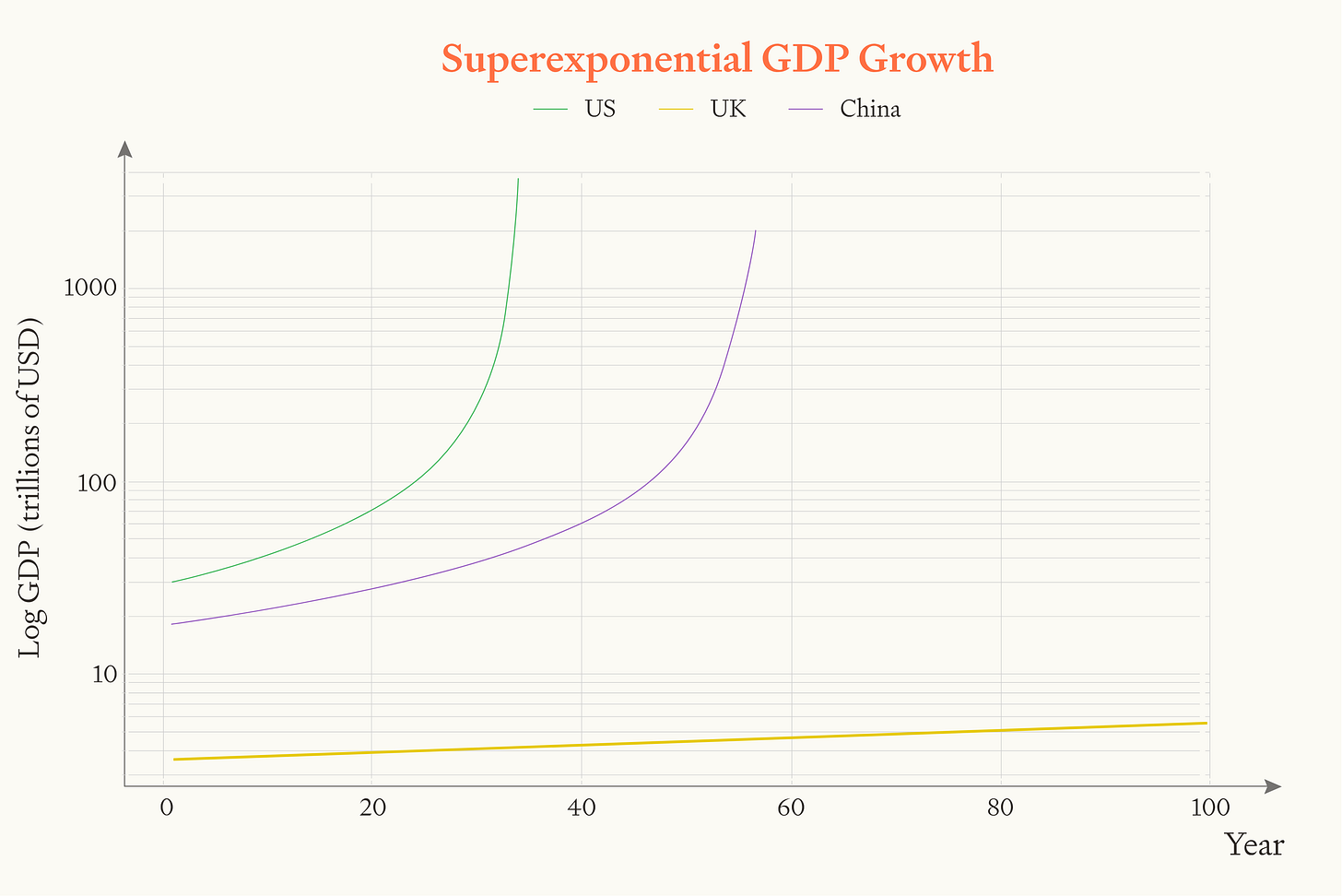

First, the Superexponential Growth Argument. After developing AGI, economic growth may become faster and faster over time – superexponential growth. If countries follow superexponential growth trajectories, an initial economic lead becomes bigger and bigger over time. The leader eventually produces >99% of global output.

I consider a series of objections to this argument and find one of them fairly convincing: laggards might keep up via “technological diffusion”, copying technologies that the leader worked hard to develop.

My tentative conclusion here is that the leading AI country (i.e. the US or China) likely could outgrow the rest of the world, but only if it makes a concerted and well-coordinated effort to prevent technological diffusion. Whether the leading AI country will in fact make such an effort is unclear. The most likely way this happens is probably that a coalition of US+allies extend current export controls on AI chips to outgrow authoritarian countries.

Second, I discuss the Grabbing New Resources Argument. A country could outgrow the world by seizing control of unclaimed resources, especially in space. Less than 1 billionth of the sun’s energy hits earth. If a country dominates the solar system, they’ll dominate economically. A key uncertainty here is whether grabbing space resources involves a winner-takes-all dynamic (e.g. if a country with 60% of world GDP could grab >90% of the solar system’s resources). Absent such a dynamic, grabbing space resources could allow a country to lock in its dominance, but not to become dominant in the first place.

Lastly, an appendix quickly discusses whether just one company could outgrow the rest of the world. This is less likely than a country, but strikingly plausible.

The Superexponential Growth Argument

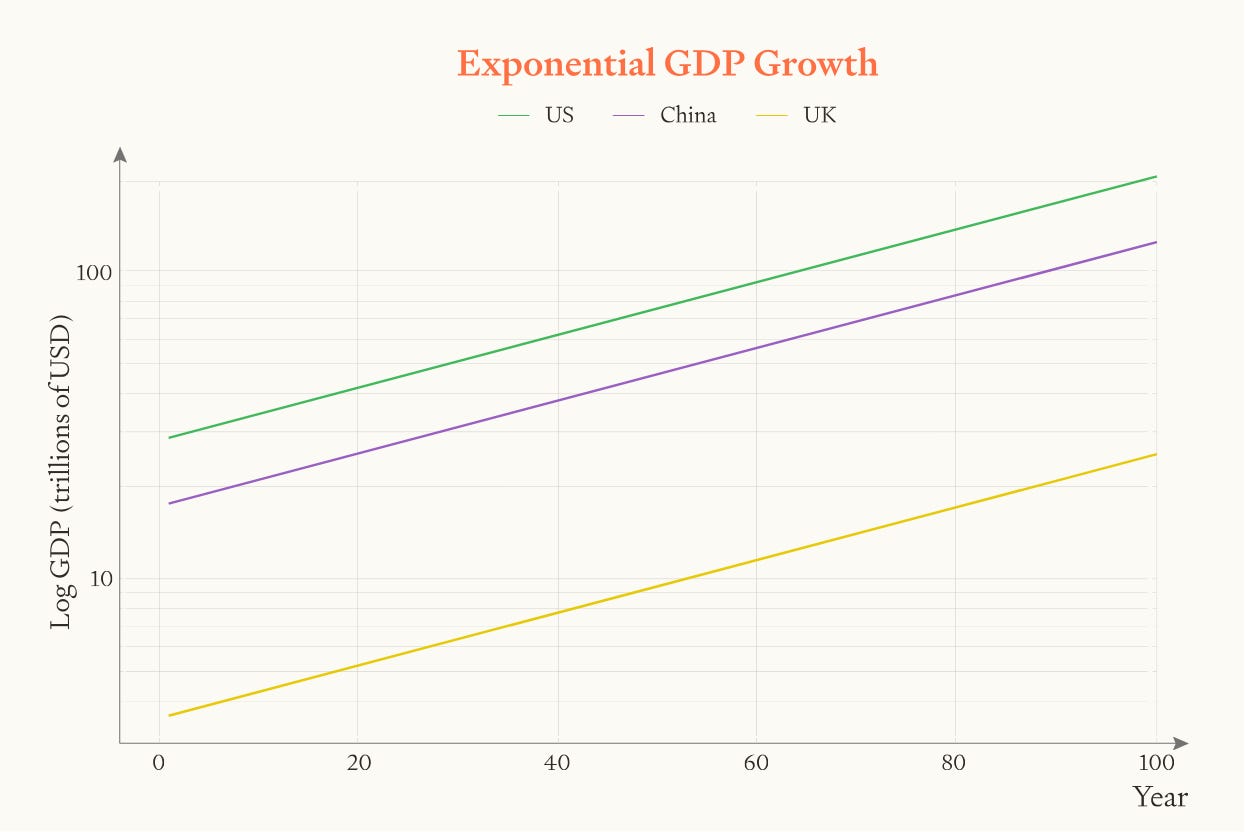

In recent history, economic growth has been roughly exponential. Countries have doubled their output roughly every 30 years.

Under exponential growth, the relative size of different countries’ GDP is constant over time. If US GDP is 8X bigger than UK GDP today, and both countries grow at the same exponential rate, then this 8X gap won’t change over time.

As we transition to AGI (including automating both cognitive work and physical labour), there’s good reason to think that growth will become superexponential, with the growth rate increasing continuously over time. The key argument here is that AGI allows us to invest economic output into creating more labour, which unlocks a powerful feedback loop of more output → more labour → more output… This new feedback loop (in combination with already-existing economic feedback loops) drives superexponential growth. (Though most economists don’t expect AGI to cause a significant acceleration in growth – see discussion here and here.)

Let’s start with a simplified set-up where there’s no trade and no technology diffusion between countries. In this scenario, if the growth of each country becomes superexponential, then an initial lead in GDP will amplify over time as the bigger country will grow more quickly.

Naively, whichever country starts off the biggest will eventually outgrow the rest of the world, becoming an arbitrarily large fraction of world GDP. (Though we’ll see below that this scenario is unrealistic in many respects.)

For this superexponential growth dynamic to allow a country to become the vast majority of world GDP, growth would have to eventually become very fast. Economic output would have to double every couple of years.1 But it seems plausible to me that, in the limit of technology, both cognitive labour and physical infrastructure could double much faster than this, in mere weeks.

Ok, that’s the basic Superexponential Growth Argument for thinking that one country could outgrow the world. Now let’s go through a series of objections.

Objection 1: What about trade?

In the previous scenario, the growth rate of each individual country depended on its own output. Bigger countries grew faster. That would make sense if countries were self-contained economic units, with the inputs to growth coming only from within.

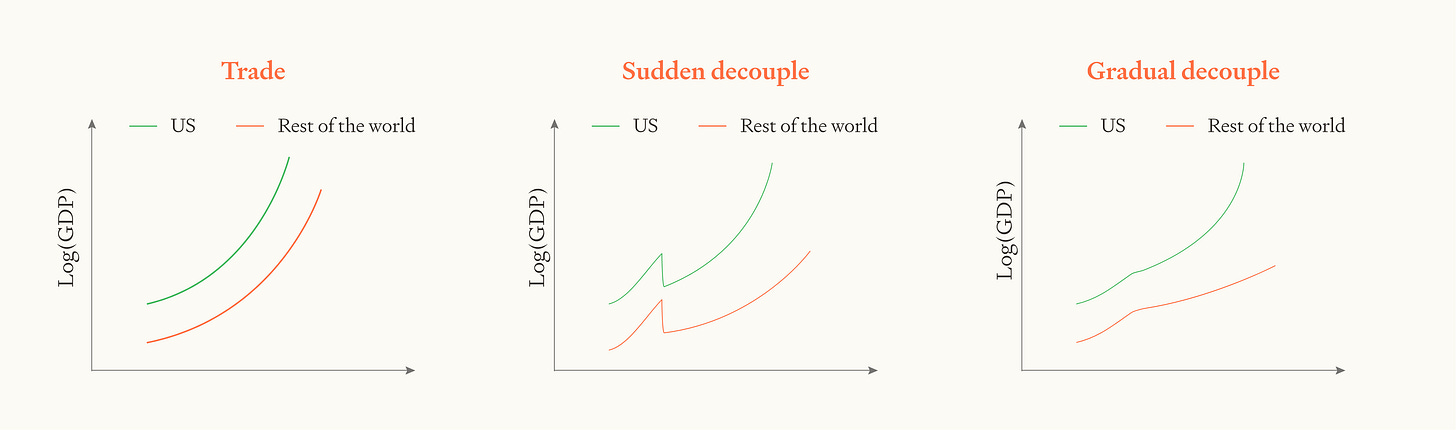

But in fact, countries trade. If the US and UK trade extensively, then the relevant economic unit is not one individual country, but the combined economy of US+UK. Rather than “bigger countries grow faster”, we’ll see “bigger trading blocs grow faster”.

For example, the US is the world’s biggest economy at ~25% of GDP. Let’s assume it stays at 25% as the world enters a period of superexponential growth. Accounting for trade, the US couldn’t “go it alone” and outgrow the world. The rest of the world could form a trading bloc with 75% of GDP and outgrow the US.2 (In this toy example, all the world simultaneously gets access to AI technology that allows it to start growing superexponentially, ignoring the fact that some countries lead on AI.)

This doesn’t mean that outgrowing the rest of the world is impossible. It just means that you need to start off with >50% of world GDP to do it. In this case, you could simply not trade with the remaining <50% and still ultimately outgrow them. And then if you do want to trade (because there are still big gains from trade), you have a strong BATNA and could in theory only accept trades that maintain your ability to outgrow the rest of the world (though we’ll see below that in practice this might be tricky due to technological diffusion).

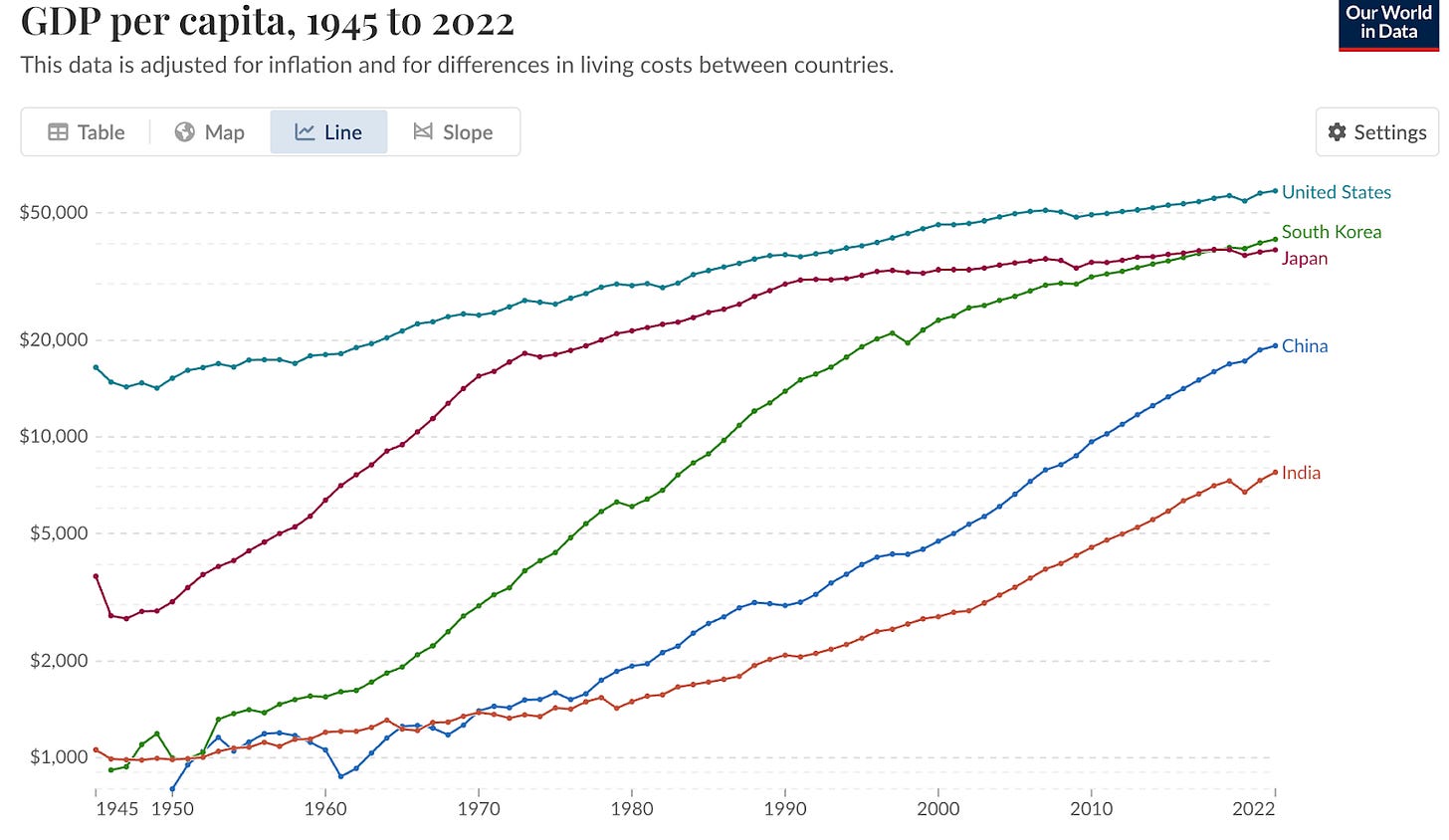

So, could one country outgrow the world? It’s quite plausible that the US could rise to >50% of global output given its lead on AI. During the industrial revolution, Britain’s share of world GDP increased by 8X;3 a similar increase during the AI transition would put the US at about 70%.4 And similarly, if China ends up leading on AI then they might rise to >50%, especially if developing superintelligence requires a massive industrial buildout.5

Even if no individual country has >50% of GDP, a trading bloc might do so. US + allies already have >50% of GDP.6 So they could form a trading bloc and outgrow the rest of the world.

That’s the first objection. The Superexponential Growth Argument still goes through, but we need one country (or trading bloc) to start with >50% of GDP. That’s a lot, but it’s still a plausible assumption. On to the next objection!

Objection 2: But no country is self-sufficient!

The economic models I’ve been using are obviously very oversimplified. Like many economic models, they treat “output” as a simple scalar quantity. Whereas in reality, there are many distinct types of output (roads, EUV machines, solar panels, robots) and you need many such outputs to sustain growth.

And, importantly, no one country can produce every type of essential output. For example, the semiconductor supply chain is incredibly complicated, with many distinct essential steps that are performed in different countries across the globe. No one country could make semiconductors all by themselves without a massive short-term productivity hit.

How does this affect the analysis?

It means that the gains from trade discussed above will likely be very large. Cutting off trade entirely requires recreating essential steps of production from scratch, with significant impact on total output in the short-term. Imagine the US having to rediscover all the progress made by ASML before it can produce more chips. So a sudden “no-trade” scenario is unlikely.

This doesn’t mean one country couldn’t outgrow the world. Again, consider the US and imagine that after AGI it’s >50% of GDP. If it suddenly ceases trade with the rest of the world, the outcome might be that all countries take a 3X short-term hit to output, still leaving the US with >50% of world output and on track to outgrow the world. With that strong a BATNA, the US might negotiate a trade deal that avoids that short-term hit to output for everyone, but leaves the US with the ability to ultimately outgrow the world. Or the US might gradually decouple from the rest of the world, such that its output never falls in absolute terms but its growth slows (relative to the counterfactual without decoupling). Gradual decoupling seems especially plausible.

It might seem unlikely that a country would accept any significant counterfactual decrease in its short-term GDP, even for the promise of future economic dominance. But GDP growth will already be unprecedentedly high. And the cost may be very short lived. If GDP eventually doubles every year or even every week, it will not be long before the country’s economy has recovered and it has become economically dominant. A few weeks of slower growth may seem a very small price to pay for economic dominance over rival nations!

That’s the second objection. It suggests that cutting off trade with other countries might be quite costly. But it’s realistic that a country would pay that cost. It could be a relatively small, temporary cost, well worth the benefit of economic dominance. And, with this strong negotiating position, a leading country might negotiate a trade deal where it avoids this cost entirely and can still outgrow the world. So I’m not convinced by this objection.

Objection 3: What about technological diffusion and stealing?

If you’re on the technological frontier, you have to do the difficult work of making scientific and technological discoveries. R&D is hard. By contrast, if you’re behind the frontier, you can potentially just steal or copy the new technologies that others have already discovered.

Indeed, during the 20th century many countries saw rapid “catch up growth”, where countries behind the economic frontier like China and Japan grew much more quickly than those at the frontier (e.g. the US) by adopting existing technologies.

More recently, the Chinese model DeepSeek-R1 was developed by copying (and improving upon) the training techniques developed by US companies. And China will no doubt benefit from TSMC’s innovations when developing its own semiconductor supply chain.

The same forces that have historically driven catch-up growth will make it harder for one country to outgrow the world. The leading country must discover new technologies from scratch; other countries can just copy their discoveries.

Of course, if the leading country is specifically trying to outgrow the world (rather than to just increase their own absolute level of GDP7), they could take steps to block tech diffusion. They could guard new technologies much more closely.

I don’t know how hard this would be. But it might be extremely hard. Even just OAI’s announcement of o1, with the graph of performance vs inference compute, made o1-style systems much easier to reproduce. If you sell API access to your AI, other countries can train their models on your trajectories. Blocking spies is hard. Preventing hacking is hard. For physical artefacts like chips or phones or robots, it seems unrealistic to prevent another country from obtaining any copies that they could disassemble and learn from.

At the very least, blocking technological diffusion would require a large government effort. Suppose the US develops AGI. Individual US businesses will compete to sell new technologies, both digital services and physical artefacts, to the broader global market. The US government would need to block many such sales, even though those sales would increase US GDP. (Blocking the sales would decrease US GDP but increase the US’ fraction of future world GDP by preventing technological diffusion.8)

If the US was one perfectly coordinated actor that specifically wanted to outgrow the world, then perhaps it would make this large effort. But the US is not (currently!) coordinated in this way. Competitive dynamics within the US will drive technological diffusion, making it harder for the US to outgrow the world.

Further, a strongly coordinated effort to outgrow the rest of the world would conflict with many US values. People in the US value prosperity, freedom, liberalism, justice and democracy. Forcibly excluding other democratic countries from trade so that the US can dominate, and making the whole world (including the US) poorer in the process, would be unappealing to many elements of US society.

One reason the US might make a strongly coordinated effort to outgrow the rest of the world is if a small group stages a coup. The group might be generally power-seeking and so explicitly aim to outgrow the world. They could also obtain an unprecedented degree of control over the US by having obedient AIs automate the government and broader economy. With this control, they could block trades that enable technological diffusion.

Another possibility is that a trading bloc consisting of US + allies coordinate to outgrow authoritarian countries for ideological or national security reasons. This has already started to some extent with export controls on AI chips. If the US + allies restrict access to AGI, that could be sufficient for them to outgrow the world. And likewise, if China ultimately leads on AI then a China-led trading bloc might outgrow the world.

That’s the third objection. Preventing tech diffusion would in my opinion require a large and coordinated effort. That might happen if a small group stages a coup and explicitly tries to outgrow the world. Or it might happen if a US-led bloc tries hard to outgrow authoritarian countries.

This is the part of this piece where I have the most uncertainty. I don’t know how strong and rapid the forces of technological diffusion will be in a post-AGI world. I don’t know how much effort it would take to block those forces. And I don’t know how much effort a country will make. The box below has some additional thoughts on why I expect a lot of technological diffusion by default.

An argument for expecting significant technological diffusion

Now I’ll consider a final objection.

Objection 4: Wouldn’t outgrowing the world set a dangerous precedent?

Imagine there are 100 people, each of whom control an equal fraction of GDP. The Superexponential Growth Argument tells us that 51 of them could get together, make a trading bloc, and completely outgrow the other 49.

So now 49 people have fallen into economic irrelevance and 51 remain. What’s then to stop 26 of the remaining people repeating the process? They could get together and outgrow the other 25. And once they’ve done that, the process could repeat again!

We might expect people to anticipate all of this in advance. They might prefer a regime where no faction ever outgrows the rest to a regime where they initially increase their share of world GDP but are later made economically irrelevant.

Similarly, a trading bloc of countries might worry that if they outgrow the rest of the world, they’d be setting a precedent for a subset of the bloc to later break away.

This is an interesting objection. But there’s a few ways it could fail:

Risk-taking. The trading bloc might choose to outgrow the world despite this risk. This is similar to how groups stage coups, despite this setting a precedent for breaking the law and increasing the risk they are later ousted.

Ideology. The trading bloc might be united around some common ideology that drives their decision to outgrow the rest of the world – e.g. democracy or liberalism. They might reasonably expect that no subset of the bloc will later coalesce around a similarly motivating ideology that excludes them.

Credible commitments. The countries in the trading bloc might all use AI-enabled technology to credibly commit to never splinter again.

Government power. It might be just one country that outgrows the world. That country needn’t worry about 51% of its economy “splintering off” to outgrow the other 49% because the government could stop it.

Points #2 and #4 seems especially compelling to me.

Assessing the Superexponential Growth Argument

The table below summarises the basic Superexponential Growth Argument and the objections that I’ve considered.

Overall, I think the Superexponential Growth Argument is pretty strong, especially for a trading bloc. But I don’t know if it succeeds because the technology diffusion objection seems strong.

Now I’ll turn to another distinct argument for thinking that a country could outgrow the world – the Grabbing New Resources Argument.

The Grabbing New Resources Argument

To outgrow the world, a country could simply seize control of unclaimed resources like the high seas, patents, and (especially) non-earth based solar energy. Only 1 billionth of the sun’s energy lands on earth. When technology makes it feasible to enter space and harness all the sun’s energy, that could increase output by a factor of 1 billion (assuming raw materials aren’t a bottleneck). A country could use a temporary technological, economic or military lead to grab all the resources of the solar system. This would leave them controlling >99.9% of resources, an extremely strong position from which they could plausibly ensure they eventually control all resources beyond the solar system.

One key question here is: could a country seize >99% of the solar system’s energy without already being >99% of world GDP?

You might expect that, if the US was 60% of world GDP, then they’d only be able to grab 60% of new resources. Especially if other countries anticipate that, if they let the US grab everything, the US will become strong enough to completely dominate them. If so, the process of grabbing new resources won’t extremize world GDP at all.

On the other hand, the US might be able to credibly commit that they won’t infringe on other countries’ sovereignty. And there might be first-mover advantages, or winner-takes-all dynamics in grabbing space resources. I won’t try to settle this here.

Even if grabbing new resources doesn’t extremise world GDP – even if each country grabs the same fraction of space resources as their GDP – still, grabbing new resources could play a critical role. It could make an otherwise temporary imbalance in GDP permanent. Suppose that, due to the dynamics of the Superexponential Growth Argument, the US is far ahead on technology and so is 90% of world GDP. Absent grabbing new resources, they will eventually hit the ultimate limits on technology and stop growing. Other countries will then catch up. Their large lead in GDP will be temporary. But suppose instead that they grab the resources of the solar system while they’re 90% of GDP. This would convert their temporary technological lead into a permanent lead in the fraction of resources that they control.

So the Grabbing New Resources Argument shows two things:

A country could convert a temporary economic lead into a permanent lead by grabbing space resources in proportion to their GDP. If they’ve already outgrown the world via other means (e.g. the Superexponential Growth Argument), they could make it permanent.

A country could increase their fraction of world GDP if there are winner-takes-all dynamics in grabbing space resources.

It’s unclear whether there are such winner-takes-all dynamics, but it seems plausible.

Conclusion – could one country outgrow the rest of the world?

Outgrowing the world is an interesting path to a decisive strategic advantage because it doesn’t require aggressive behaviour towards other nations.

The Superexponential Growth Argument is pretty strong. It’s plausible that the country that leads on AGI will end up as >50% of world GDP, especially if they prevent other countries from developing near-frontier AI. From there, they could outgrow the rest of the world, but only if they’re able to sufficiently block technological diffusion. This might take a very large effort and a significant degree of internal coordination. That effort might be made by a US-led trading bloc trying to exclude authoritarian countries, or by a power-seeking group that has staged a coup. Ultimately, I’m pretty unsure whether technological diffusion will prevent the US (or a US-led bloc) becoming >90% world GDP.

Then the Grabbing New Resources Argument comes in. The US will likely be a large fraction of world GDP and have a decent technological and military lead. It could likely make this lead permanent, and perhaps increase its fraction of GDP further, by grabbing the resources of the solar system.

As a reminder, I’ve purposefully set aside non-economic considerations, like whether a country could gain dominance militarily, or whether other countries would intervene militarily to stop a country from outgrowing the world.

Bonus – what about one company outgrowing the rest of the world?

This isn’t likely, but does seem surprisingly plausible to me. Here’s how it could happen.

First, a frontier AI company establishes a monopoly on frontier AI. The leading company might get a temporary lead by being the first to automate AI R&D and having a spurt of rapid algorithmic progress. They might embed this lead by buying up the vast majority of AI compute – e.g. because their far-superior demos attract more investment, or because they can make significantly more productive use of that compute with their superior algorithms. Alternatively, they could embed the lead by lobbying the government for favourable regulation or even by sabotaging their rivals’ development efforts (e.g. cyber attacks).

Maybe these strategies allow the company to maintain their monopoly on frontier AI for months or years, during which time they fiercely lobby the government (pointing out that disruption would have severe economic consequences), fight in court to avoid antitrust actions, and try to make the government overreliant on their services.

If the company gains this monopoly then they will ultimately control ~100% of the world’s quality-adjusted cognitive labour.9 To outgrow the world, they need to be able to produce >50% of the world’s GDP by themselves. But GDP isn’t just produced by cognitive labour alone – you need complementary physical actuators. This brings us to the company’s next step.

Second, the company acquires >50% of the world’s physical capital. This is a big lift. Physical capital, and the know-how of how to produce it, is currently highly distributed. The company needs to aggressively leverage its advantage in cognitive labour to achieve this.

We can think of this as a race against time. Within a few months or years, the company may lose its monopoly on cognitive labour – another company may automate AI R&D and acquire a similar amount of computer chips.10 Before that time, the company needs to acquire more physical capital than the rest of the world combined. They can’t buy the physical capital directly – even spending $1 trillion / year (which is more than USG spends on physical capital!) wouldn’t be enough to overtake the rest of the world, which has a total productive physical capital stock of ~$400 trillion.11

So the critical question is whether the company could quickly build physical capital that self-replicates very rapidly – rapidly enough that the company controls >50% of the world’s physical capital by the time they lose their edge on cognitive labour. Let’s generously assume that they acquire $1 trillion of physical capital and then (having acquired it) have a further 9 months to grow it to above the $400 trillion of physical capital controlled by the rest of the world. In this case, they’d need the capital stock to self-replicate once per month. ($1tr * 2^9 = $512tr.)

This toy spreadsheet model allows you to play around with the assumptions for this calculation.

I’d bet against physical capital self-replicating this quickly immediately after AGI – here I estimate that after AGI physical capital will have a ~one year doubling time. But it might be possible, for example if AGI can make very rapid technological progress.

Edited to add: I now think the right AI capability to consider for this is thought experiment is not AGI but the capability we have just after the software intelligence explosion. As a result, I think it’s more plausible that physical capital will double sufficiently quickly for the company to outgrow the world. See here for discussion.

During this second step of acquiring physical capital, the company would again have to lobby hard to resist government intervention. (And of course, the government would have very strong national security reasons to intervene, as the company would be gaining significant industrial might that could be converted into military power.)

Compared to a country, a company is more likely to be well coordinated internally and so more likely to only do trades that help it outgrow the world. Technological diffusion will be less of a problem.

Overall, I think it’s plausible a company could outgrow the world, but unlikely. They’d need to establish a strong monopoly on frontier AI and quickly develop very powerful self-replicating physical technologies, all without government intervention.

Thanks very much for comments from Damon Binder, Max Dalton, Ryan Greenblatt, Rose Hadshar, Basil Halperin, Tom Houlden, Chad Jones, William MacAskill, Fin Moorhouse, Phil Trammell, and Lizka Vaintrob.

Why every couple of years? Suppose two countries are both following the same superexponential growth trajectory. The leader starts off with its GDP 50% bigger than the laggard. Then, at today’s 3% growth rate, the leading country is 14 years ahead. As both countries progress along the same superexponential trajectory, the leader will remain 14 years ahead. But, as growth accelerates, the size of its GDP lead increases. If GDP eventually doubles every 2 years then the leader will be 7 doublings ahead of the laggard – a factor of 128. The leader would be >99% of their total GDP.

Couldn’t the US trade with the individual countries in this trading bloc in such a way that US GDP rises above 50%? I’m skeptical. Suppose the US has 25% of world GDP, and the rest of the world are trading with each other. If the US doesn’t trade with the rest of the world, their fraction of world GDP will shrink, eventually to 0%. This is not a strong BATNA from which the US can negotiate trades that significantly increase its fraction of world GDP. In addition, there’s a very natural and fair-seeming deal in which the gains from trade are split so as to keep countries’ share of world GDP constant. And indeed, over the past 100 years the US hasn’t traded its way to a majority of world GDP.

Currently the ratio of GDP US:RoW is 1:3. If US GDP increased by a factor of 8 then this would be 8:3. The US would produce 72% of world GDP.

China produces around 20% of world GDP, so the ratio of GDP between China and the rest of the world is currently 1:4. Increasing by a factor of 8 would be 8:4, or two thirds of world GDP.

Wait, wouldn’t outgrowing the world be the best way to maximise your country’s GDP? Not in the short term. Maximally increasing your GDP involves trades which lead to technological diffusion. The trades make your country richer, and make the global economic pie bigger, but they decrease your country’s fraction of the pie. If you’re specifically trying to outgrow the world, you’d avoid these trades. You’d be poorer counterfactually, but a bigger fraction of world GDP. And, in the long-run, you might eventually be richer if world GDP hits a plateau and you have a bigger fraction at that plateau. (Though you might not be, if continued trade allows the world to reach a higher plateau, as it does with today’s technology.)

Wait, didn’t we say earlier that because the US’ BATNA here is outgrowing the world, they should be able to find a win-win trading deal where they still outgrow the world? Yes, but there we were imagining that the US and the rest of the world (RoW) were both unified actors. In that case, the US could in principle share technological insights with RoW at a high price, both US and RoW would benefit, and the US would still outgrow RoW. But in this paragraph we are discussing deals between a US firm and a RoW firm. Such deals have a large positive externality for RoW due to the technological diffusion: not only does the recipient firm get to use the technology directly, the RoW learns more about how to create that technology themselves. Such firm-to-firm deals help the US firm and the RoW firm directly, but the externality reduces the US’ share of future global GDP. So, to outgrow the world, the US would need to ban such deals and only sell its technology when RoW pays the US for the positive externality (which should be possible in principle, but would require a lot of very impressive coordination).

AI cognitive labour will eventually dwarf human cognitive labour and the company controls ~100% of AI cognitive labour, so they’ll control ~100% of all cognitive labour.

The company could try to maintain their monopoly indefinitely by continually buying up the world’s supply of compute or by sabotaging other projects. If it succeeded, outgrowing the world would be much easier.

Based on ~$100 trillion world GDP and a capital-to-GDP ratio of 4.

I'd be a bit cautious *contrasting* the US with "authoritarian countries" given some of the statements and actions of the Trump admin (though yes, the US would have to change a lot to be as authoritarian as China.)