Should we aim for flourishing over mere survival?

The Better Futures series.

Today Forethought and I are releasing an essay series called Better Futures, here.1 It’s been something like eight years in the making, so I’m pretty happy it’s finally out! It asks: when looking to the future, should we focus on surviving, or on flourishing?

In practice at least, future-oriented altruists tend to focus on ensuring we survive (or are not permanently disempowered by some valueless AIs). But maybe we should focus on future flourishing, instead.

Why?

Well, even if we survive, we probably just get a future that’s a small fraction as good as it could have been. We could, instead, try to help guide society to be on track to a truly wonderful future.

That is, I think there’s more at stake when it comes to flourishing than when it comes to survival. So maybe that should be our main focus.

The whole essay series is out today. But I’ll post summaries of each essay over the course of the next couple of weeks. And the first episode of Forethought’s video podcast is on the topic, and out now, too.

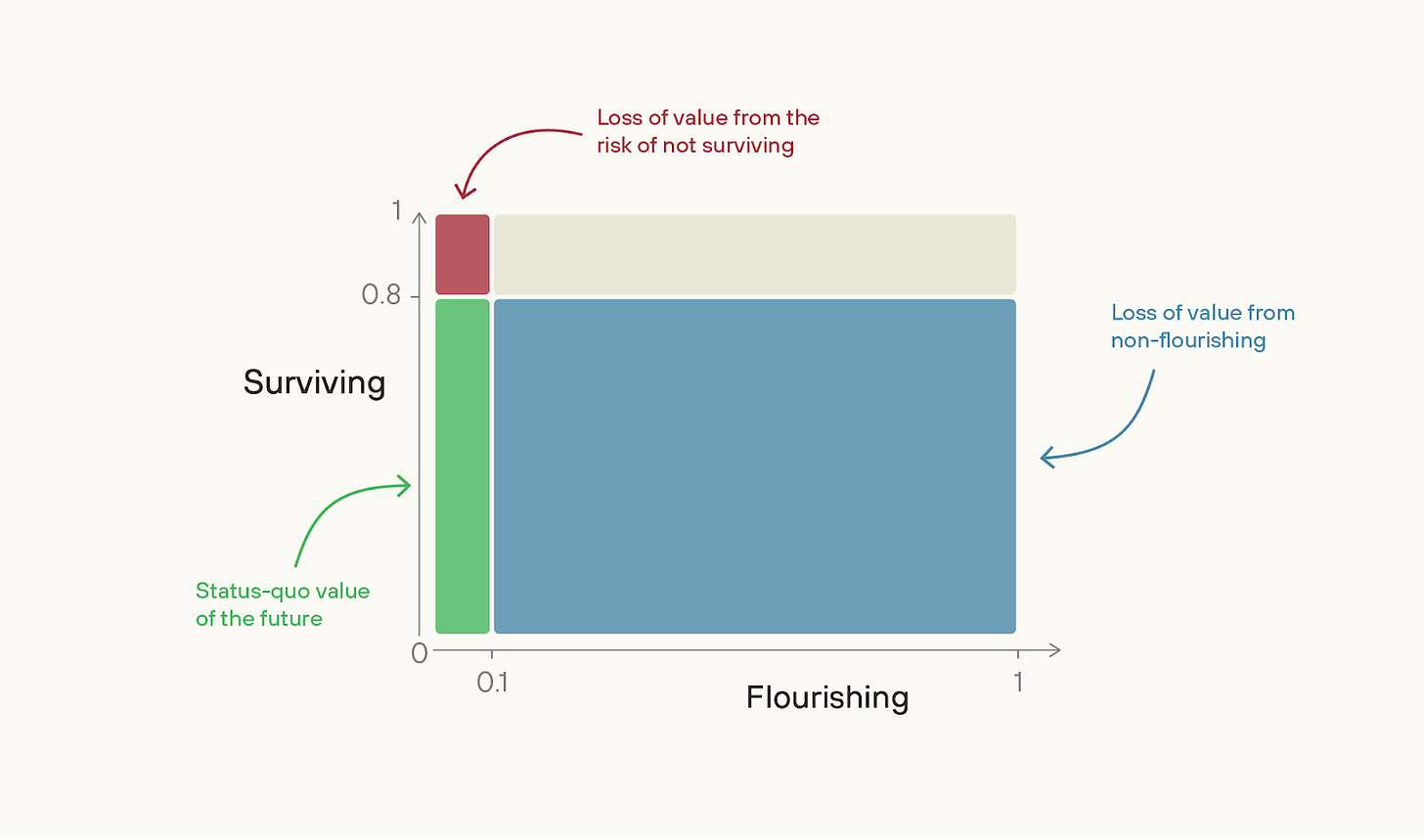

The first essay is Introducing Better Futures: along with the supplement, it gives the basic case for focusing on trying to make the future wonderful, rather than just ensuring we get any ok future at all. It’s based on a simple two-factor model: that the value of the future is the product of our chance of “Surviving” and of the value of the future, if we do Survive, i.e. our “Flourishing”.

(“not-Surviving”, here, means anything that locks us into a near-0 value future in the near-term: extinction from a bio-catastrophe counts but if valueless superintelligence disempowers us without causing human extinction, that counts, too. I think this is how “existential catastrophe” is often used in practice.)

The key thought is: maybe we’re closer to the “ceiling” on Survival than we are to the “ceiling” of Flourishing.

Most people (though not everyone) thinks we’re much more likely than not to Survive this century. Metaculus puts *extinction* risk at about 4%; a survey of superforecasters put it at 1%. Toby Ord put total existential risk this century at 16%.

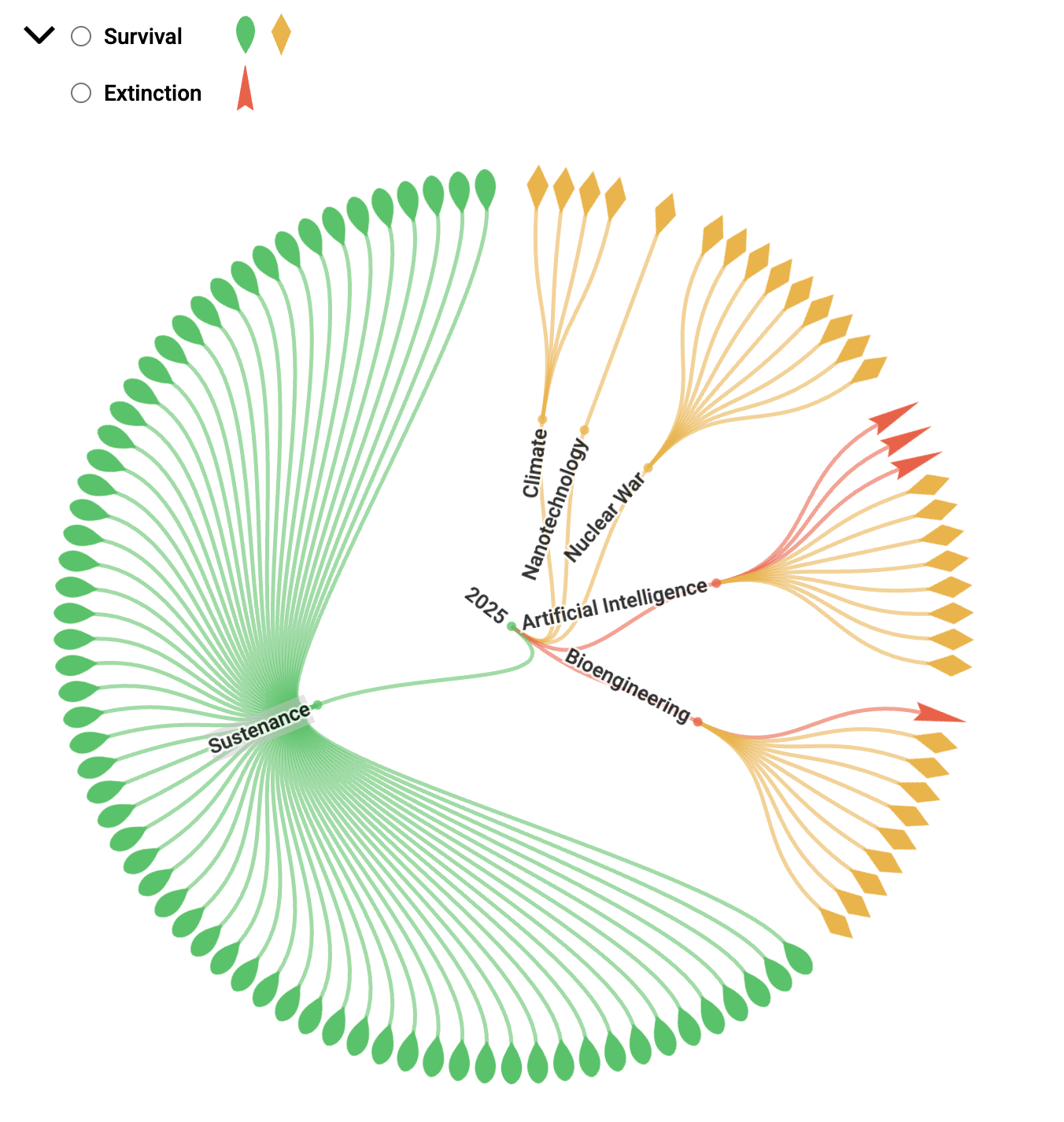

Chart from The Possible Worlds Tree.

In contrast, what’s the value of Flourishing? I.e. if near-term extinction is 0, what % of the value of a best feasible future should we expect to achieve? In the next two essays that follow, Fin Moorhouse and I argue that it’s low.

And if we are farther from the ceiling on Flourishing, then the size of the problem of non-Flourishing is much larger than the size of the problem of the risk of not-Surviving.

To illustrate: suppose our Survival chance this century is 80%, but the value of the future conditional on survival is only 10%.

If so, then the problem of non-Flourishing is 36x greater in scale than the problem of not-Surviving.

(If you have a very high “p(doom)” then this argument doesn’t go through, and the essay series will be less interesting to you.)

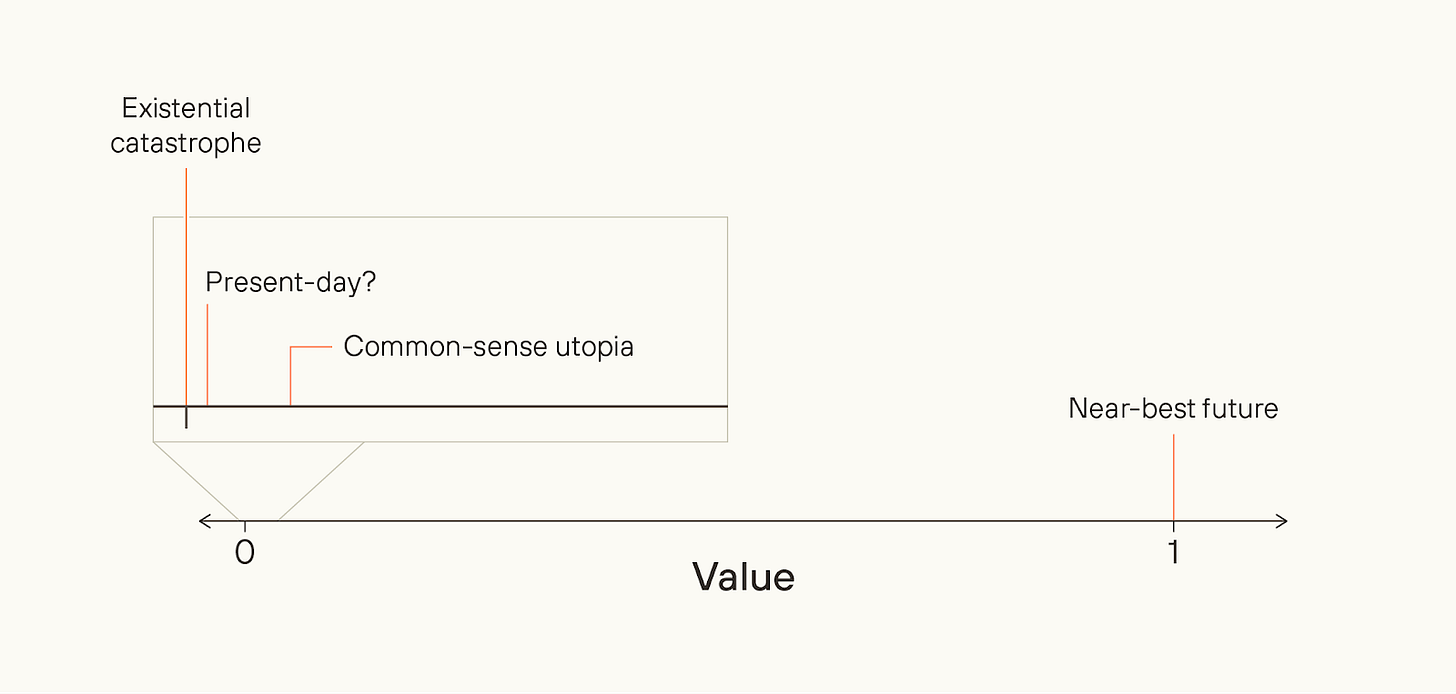

The importance of Flourishing can be hard to think clearly about, because the absolute value of the future could be so high while we achieve only a small fraction of what is possible. But it’s the fraction of value achieved that matters. Given how I define quantities of value, it’s just as important to move from a 50% to 60%-value future as it is to move from a 0% to 10%-value future.

We might even achieve a world that’s common-sensically utopian, while still missing out on almost all possible value.

In medieval myth, there’s a conception of utopia called “Cockaigne” - a land of plenty, where everyone stays young, and you could eat as much food and have as much sex as you like.

We in rich countries today live in societies that medieval peasants would probably regard as Cockaigne, now. But we’re very, very far from a perfect society. Similarly, what we might think of as utopia, today, could nonetheless barely scrape the surface of what is possible.

All things considered, I think there’s quite a lot more at stake when it comes to Flourishing than when it comes to Surviving.

I think that Flourishing is likely more neglected, too. The basic reason is that the latent desire to Survive (in this sense) is much stronger than the latent desire to Flourish. Most people really don’t want to die, or to be disempowered in their lifetimes. So, for existential risk to be high, there has to be some truly major failure of rationality going on.

For example, those in control of superintelligent AI (and their employees) would have to be deluded about the risk they are facing, or have unusual preferences such that they're willing to gamble with their lives in exchange for a bit more power. Alternatively, look at the United States’ aggregate willingness to pay to avoid a 0.1 percentage point chance of a catastrophe that killed everyone - it’s over $1 trillion. Warning shots could at least partially unleash that latent desire, unlocking enormous societal attention.

In contrast, how much latent desire is there to make sure that people in thousands of years’ time haven’t made some subtle but important moral mistake? Not much. Society could be clearly on track to make some major moral errors, and simply not care that it will do so.

Even among the effective altruist (and adjacent) community, most of the focus is on Surviving rather than Flourishing. AI safety and biorisk reduction have, thankfully, gotten a lot more attention and investment in the last few years; but as they do, their comparative neglectedness declines.

The tractability of better futures work is much less clear; if the argument falls down, it falls down here. But I think we should at least try to find out how tractable the best interventions in this area are. A decade ago, work on AI safety and biorisk mitigation looked incredibly intractable. But concerted effort *made* the areas tractable.

I think we’ll want to do the same on a host of other areas — including AI-enabled human coups; AI for better reasoning, decision-making and coordination; what character and personality we want advanced AI to have; what legal rights AIs should have; the governance of projects to build superintelligence; deep space governance, and more.

On a final note, here are a few warning labels for the series as a whole.

First, the essays tend to use moral realist language - e.g. talking about a “correct” ethics. But most of the arguments port over - you can just translate into whatever language you prefer, e.g. “what I would think about ethics given ideal reflection”.

Second, I’m only talking about one part of ethics - namely, what’s best for the long-term future, or what I sometimes call “cosmic ethics”. So, I don’t talk about some obvious reasons for wanting to prevent near-term catastrophes - like, not wanting yourself and all your loved ones to die. But I’m not saying that those aren’t important moral reasons.

Third, thinking about making the future better can sometimes seem creepily Utopian. I think that’s a real worry - some of the Utopian movements of the 20th century were extraordinarily harmful. And I think it should make us particularly wary of proposals for better futures that are based on some narrow conception of an ideal future. Given how much moral progress we should hope to make, we should assume we have almost no idea what the best feasible futures would look like.

I’m instead in favour of what I’ve been calling viatopia, which is a state of the world where society can guide itself towards near-best outcomes, whatever they may be. Plausibly, viatopia is a state of society where existential risk is very low, where many different moral points of view can flourish, where many possible futures are still open to us, and where major decisions are made via thoughtful, reflective processes.

From my point of view, the key priority in the world today is to get us closer to viatopia, not to some particular narrow end-state. I don’t discuss the concept of viatopia further in this series, but I hope to write more about it in the future.

This series was far from a solo effort. Fin Moorhouse is a co-author on two of the essays, and Phil Trammell is a co-author on the Basic Case for Better Futures supplement.

And there was a lot of help from the wider Forethought team (Max Dalton, Rose Hadshar, Lizka Vaintrob, Tom Davidson, Amrit Sidhu-Brar), as well as a huge number of commentators.

Surely those in charge of AI and working to maximise that technology lever are optimising precisely for *flourishing*

"The tractability of better futures work is much less clear; if the argument falls down, it falls down here. But I think we should at least try to find out how tractable the best interventions in this area are. A decade ago, work on AI safety and biorisk mitigation looked incredibly intractable. But concerted effort *made* the areas tractable."

Has it really? Do you really think we are functionally 'safer' right now? or that somewhere in the undefined decades ahead, there is an inflection point that the work has pointed at?

I commend the looking at "flourishing" as something other than surviving, but most of this seems continually averse and maybe allergic to looking at what is happening right now in the world. I could agree more people perhaps are "talking about things in the space of wondering how to make futures better", but, has the last five years really brought things to a more tenable reality?