Which type of transformative AI will come first?

This article was created by Forethought. See the original on our website.

Introduction

“AI will be transformative” is now a pretty mainstream view. Indeed, it will be transformative in many different ways. Which of these should we pay most attention to?

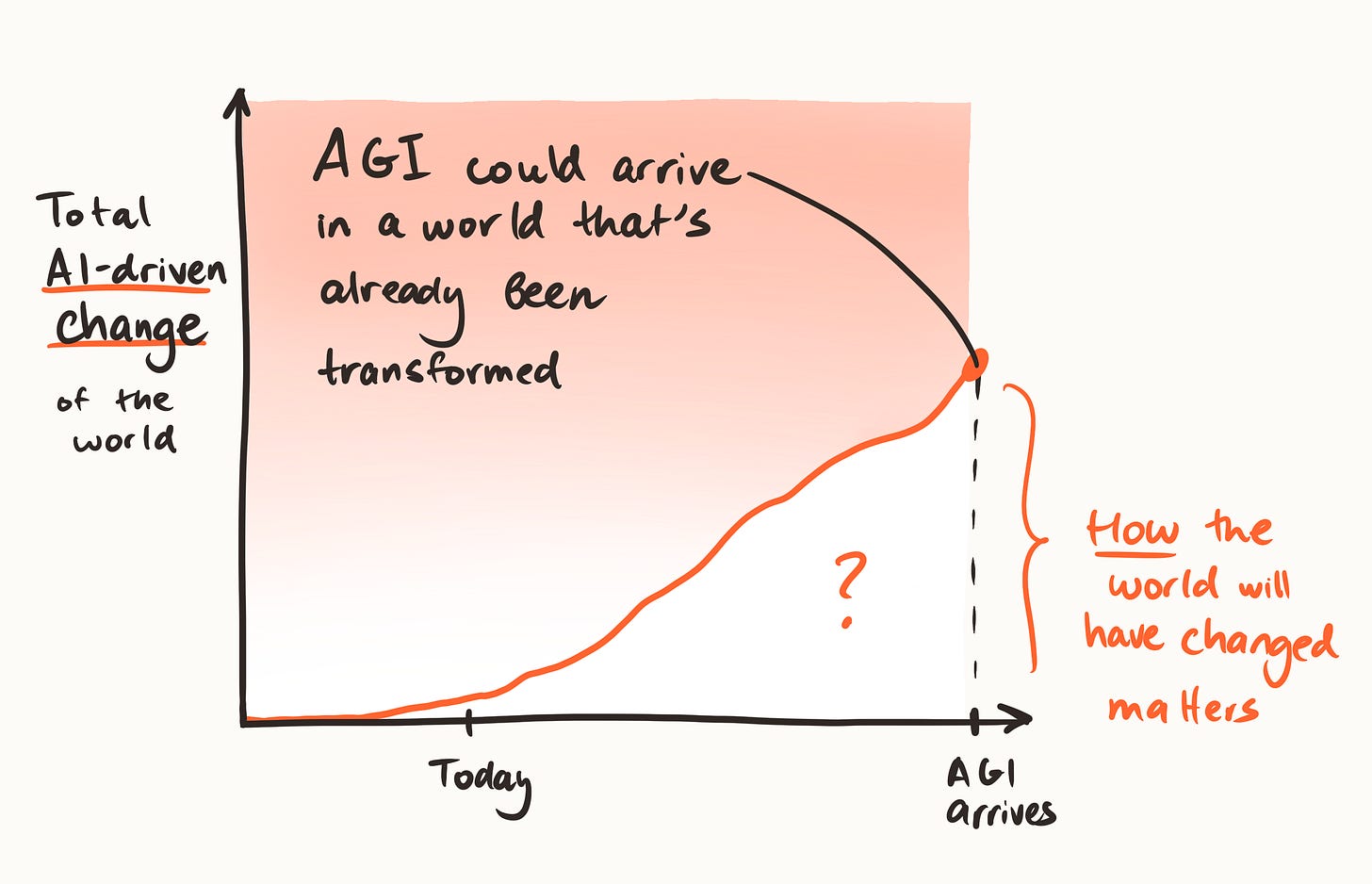

Serious discussion often focuses on the biggest challenges AI might bring — an intelligence explosion; or scheming AI systems. But AI will likely change many aspects of the world. By the time we face the biggest challenges, things might already be very different. If we want to navigate the transition well, it seems useful to understand this shifting landscape. So: in what way(s) will AI be a big deal first?

Some possible answers:

Economic

Greater economic growth and wealth

Advanced robotics reshaping manufacturing and household services

Altered resource bottlenecks (e.g. energy scarcity or glut)

Cyborg teams outperforming humans in many industries

Scientific

Accelerating medical research

Rapid uptick in technological R&D

Automation of AI research leading to intelligence explosion

Epistemic

Making strategic foresight more like weather forecasting or web search

Permitting — or fighting — personalized misinformation at scale

Replacing (& improving?) the way that people coordinate to make decisions

Power & influence

Mass unemployment & widening economic inequality

Control of militaries becoming much more centralized

Strengthening democracy by enabling greater participation and more meaningful oversight

Shifts in the equilibrium of power between states, or between companies and states

Widespread access to potentially dangerous knowledge (e.g. bioweapons, cyber) or cheap offensive equipment (e.g. drones)

~Existential

Emergence of AI systems that might reasonably be seen as moral patients

Brain emulation tech that strains our notions of personhood

Risk of takeover by misaligned agentic AI systems

Early transformations change the strategic landscape

On their own, some of the “transformations” above would matter a lot less than others. But early changes could affect who has power, how people think about AI, what tools are available to us, and so on — all of which, in turn, affects how subsequent transitions play out. So knowing the likely order of transformations could change what’s good to do.

Some illustrative trajectories

Compare, for instance, the following hypothetical paths:

Silent intelligence explosion (silent IE)

AI has modest impacts on the world, until a breakthrough triggers a rapid intelligence explosion

The world is suddenly faced with extremely advanced (possibly rogue) agentic superintelligence

Turbocharged economy

AI systems that can execute increasingly ambitious tasks drive growth across many sectors of the economy

We learn, through trial and error, to handle human-level-ish autonomous AI agents

This leads to more billionaires and trillionaires, while large numbers of people are being made redundant

Research speeds up across the board (but still needs humans)

The world absorbs and learns to handle a broad variety of advanced technologies

Social structures shift at unprecedented speed

Later an intelligence explosion begins in earnest1

Epistemics first

AI gets embedded into how we find information, make decisions, and coordinate

This is more infrastructure (something that works quietly in the background and enables things done on top of it) than tool (something that is brought out for a specific purpose at a specific time) or agent (something that independently operates towards a specified goal)

For better or for worse, more and more powerful AI systems are seamlessly built into our social platforms — increasingly, AI determines what info people see and trust

As AI systems come online that can do larger and larger tasks independently, they are smoothly integrated with this infrastructure layer

AI-created knowledge also integrates into these layers, helping many actors to better track the strategic situation they are in

Learning more about which transitions will likely come earlier should change our prioritization. For example, if we knew we were on these particular trajectories:

On the silent IE path:

AGI2 arrives in a world pretty similar to our own — key decision-making institutions won’t have changed drastically

Preparing to automate safety research seems especially important

Preparing for coordinated slowdown to stretch out the critical period may also be worth a shot

While other transformations may follow soon after, it makes more sense to defer preparation for them to a world with superintelligent AI

On the turbocharged economy path:

By the time we’re able to build AGI —

AI will be a much bigger social/political issue than it is today (but it’s unclear which AI-related issues will command the most attention)

Governments may struggle to keep up with progress in industry; more generally, quite different groups may be in power

Possible implications include —

Knowing how to leverage huge amounts of automated cognitive labor for good purposes seems especially important

Plans that assume serious political will might be more viable

It may be good to make contingency plans for the possibility that governments aren’t able to keep up with private groups, and mitigate the risk of governments being taken over or no longer acting in the interest of their citizens

On the epistemics first path:

The world will have more and better affordances:

Those who make use of the right AI systems have a much better picture of the strategic situation than anyone is able to have today

Major unforced errors will be technically avoidable

Choosing to deliberate or coordinate on large scales may become feasible

We should lay the groundwork now for plans which involve ambitious coordination to handle more-advanced-AI, and deprioritize plans that rely on specific collective sense-making and decision-making processes as they exist today

We should do more threat modelling on ways this could go wrong (e.g. many people actively misled by their AI assistants), and safeguard against those

Shouldn’t we just focus on AGI?

You might think that if AGI is ultimately the most important part of this picture, we should just keep our eye on that ball, and avoid getting distracted by other transformations. This is an implicit bet on something pretty close to the silent IE path (or on the view that the same interventions are still pretty much what you’d want on other paths — which we’ve just argued against).

Might this bet be justified? The strongest case we can see for focusing heavily on the silent IE trajectory would rest on some combination of the following beliefs:

Rapid AGI: AI is unlikely to change the world much until we’re facing extremely advanced agents, because progress towards AGI will be too fast (or too sharp) to allow for development and diffusion of other potentially transformative technologies

Leverage: We’re especially well positioned to help in worlds in which we are in fact on the silent intelligence explosion path, since AI challenges would get little attention from others in this scenario, we’d be facing an extremely high-stakes situation with a reasonably predictable strategic background, etc.

Ultimately, we don’t find these arguments very compelling:

On rapid AGI:

Today’s AI systems seem close to the kinds that could power important transformations (this is a theme we’ll return to in subsequent articles)

Technological progress rarely has large discontinuities, which suggests we should have a prior that pre-AGI systems will be capable enough to cause a lot of change3

While diffusion may cause real delays, uptake can still be swift and feel sudden after the tech reaches a certain quality level (and there are pathways around some obvious blockers)4

On leverage:

The neglectedness of AI safety on the silent IE path does mean our work could have an outsized influence, but we think there’s extra leverage on some of the other trajectories, too (see discussion below)

And whatever the theoretical case for leverage may be, in practice it seems5 like we’re often not that well positioned to help in silent IE scenarios

Overall, while we don’t think it’s clearly wrong for someone to focus on the silent IE type worlds, we don’t see the case for it as very robust — and we worry that it receives excess attention because it is in many ways easier to visualize than worlds which have undergone more radical transformation by the arrival of AGI.

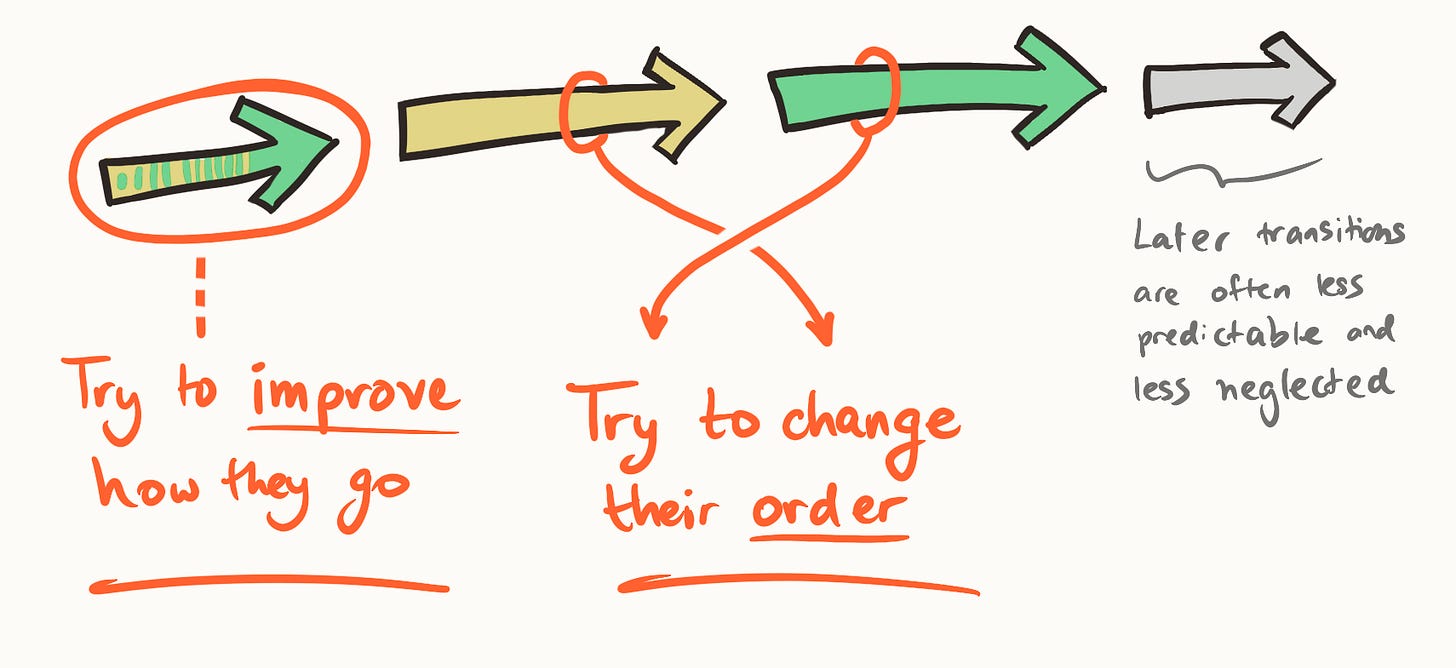

Early transformations could represent important intervention points

There are two different ways that we might try to affect early transformations to make things go better:

Changing the order of AI transformations

We’ve been treating the order of transformations as something to be discovered, but it might be pretty malleable. If a particular sequence gives us an easier path than the others — because the earlier changes would equip us to handle later challenges — then differential speedup to make it more likely that we get those sequences could help a lot. For instance:

The silent IE path seems unusually perilous

Because the risks of superintelligent AI are especially daunting; we might be better positioned to tackle them if we had capabilities/affordances granted by other AI transformations (e.g. infrastructure to help people coordinate, or to robustly automate safety work)

So if that path is somewhat likely but not overdetermined, trying to get off it by differentially speeding up other AI changes (which are more peripheral to progress towards superintelligence) could be a good idea

Epistemic infrastructure changes, meanwhile, might generally seem desirable to have early

Since getting them could increase the world’s self-awareness and capacity for deliberately handling subsequent transformations, while avoiding unendorsed emergent behaviour

We could try to make our desired sequencing more likely by differentially investing in some kinds of technology over others, working to accelerate adoption of some technologies or slow adoption of others, etc.

Improving how earlier AI transformations play out

Early AI changes might have a big impact on the world’s competence for handling subsequent challenges. And since transitions are moments of flux, there may be opportunities to help them land in good places. To improve how an early transformation plays out, we could generally try to help people understand what’s going on, and then accelerate better versions of the relevant technologies, improve key institutions, help society to integrate technology in wiser ways, etc.

For instance:

Superintelligent systems that come early on the silent IE trajectory will be able to take subsequent challenges off our hands. If we’re definitely on this path, our job is to ensure that those early superintelligent systems are aligned, safe, and pointed in good directions.

On the turbocharged economy trajectory:

The economic and scientific shifts this brings seem like they could go multiple ways:

They could mean we’ve experimented and learned good methods for deploying advanced tech, society is richer, less corrupt, more aware of AI, and more willing to invest in safety, etc.

But they could also leave us in turmoil, with a growing unemployed class and key decisions made opaquely by small groups of elites; powerful new technologies might trigger wars, etc.

So to steer towards better equilibria, we might want to e.g.

Build out technical and legal frameworks for handling ~human-level AI agents

Focus on things which help to maintain healthy balances of power among humans, help liberal governments stay relevant and legitimate, etc.

If it’s epistemics first:

If we’re not careful, AI systems that are integrated into our platforms and decision-making could manipulate or mislead instead of improving our thinking. But if we get things right, the world might be much better at handling new challenges

We might therefore work to ensure that we land in high-truth equilibria and to find ways of measuring which uplift tools are trustworthy, and drive their adoption

We may also have more leverage to improve earlier transformations (compared to improving later ones):

Later people can work on later transitions; only we can work on the early transitions

In the allocation of farsighted risk mitigation work across time, it is the comparative advantage of people before the first transformation to work on the first transformation, and of people after the first transformation to work on later ones

This consideration is stronger because the number of people paying attention to AI will probably go up over time

Moreover, work on later transitions may be swamped by huge amounts of AI labour being directed to the same questions once it’s possible to automate that kind of work (or a substitute for it)

We can make better predictions about earlier transformations (and how to affect them), and will have to pay bigger nearsightedness penalties for later transitions

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we should necessarily work on the earliest changes! For one thing, there is a spectrum of how transformative things will be (and we will tend to see small transformations before we see big ones). For another, sometimes we might need to get started early to prepare for later transitions.

Information about the likely sequencing of transformations would be valuable

Since (it seems to us) some of the best interventions available to people today may look like shaping early transformations, we think better information could have a large and direct impact on prioritization.

From our perspective, people are really dropping the ball here. We think understanding early AI transformations would be at least as action-guiding as understanding AI timelines. But questions of early transformations appear to have had much less explicit attention — instead, many people planning around the future of AI appear anchored to some implicit or received wisdom which emphasises only the most rapid and decisive transformations.6 Others (perhaps reactively) dismiss the prospect of rapid transformations entirely.

Like AI timelines, we think this is a hard question to approach. But like AI timelines, we think that careful analysis and considering different models can provide meaningful insight, and is worth some effort.

Some factors to consider when thinking about sequencing:7

Technical requirements: What technological capabilities are needed for each transformation? (Are there shorter paths? What breakthroughs are needed? Thinking about AI timelines is relevant here, but it may be ideal to examine the models underlying timeline predictions.)

Attention and investment: Are people already pushing towards the tech? Is anyone incentivised to do so, later? Might there be barriers, like social or political pushback?

Time-to-transformation: How rapidly would a tech be finessed, deployed, adopted? Are there other constraints or delays to reshaping the world? (Note that it can be hard to properly anticipate big transitions!)8

Comparison: Does the existence of one tech imply some probability of another already existing or being in use?

Deliberate strategic effort: Could technologists and funders deliberately direct attention, investment, and other prerequisites toward one or another tech pathway, because of its anticipated effects? Could societal conversations shape demand and therefore differential viability?

Closing thoughts

In future articles, we plan to go deeper on object-level analysis related to the question of some potential early transformations. In particular, we’ve come to believe that, before we see anything like agentic superintelligence, AI technologies could reshape the way people make sense of the world and make decisions. We might see exploratory, buggy tech giving way to applications that (like social media) change people’s interactions on a broad scale but don’t much change the global gameboard — and then to something more extraordinary, in the reference class of literacy, computers, or liberal democracy.

In our view, these shifts in epistemics and coordination are key early transformations to better understand and shape — ones that can too easily be obscured when we orient directly to agentic AGI and its precursors. But we are more confident in the importance of the sequencing question than in our tentative answers, so wanted to make the case for it stand alone.

In short, our case has been:

There are multiple plausible candidates for “early big impacts of AI”.

The best opportunities to make the world better depend a lot on this sequencing.

Because early transformations change what looks effective for targeting later transformations.

And because we may have better leverage on the earlier transformations.

Despite this, there has been relatively little attention so far to the question of early impacts.

Questions of technological prediction are, of course, difficult. But the stakes here are high. We hope that it can and will receive more serious analysis.

Thanks to Raymond Douglas, Max Dalton, Lukas Finnveden, Owain Evans, Will MacAskill, Rose Hadshar, Max Daniel, Tom Davidson, and Ben Goldhaber for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

This article was created by Forethought. See the original on our website.

A piece arguing for roughly this ordering of transformations: Most AI value will come from broad automation, not from R&D | Epoch AI

Moreover, various specific reasons people have given for expecting discontinuities via which risk-posing AI systems leapfrog all other AI changes are also not very convincing to us. For instance, recursive self-improvement seems more continuous than some stories might imply.

We’ll go deeper on these points in future pieces, but here are some bits of context:

AI is getting used a decent amount already — today, about three years after the launch of ChatGPT, about a billion people use chatbots at least weekly (and the value/depth of that use seems to be increasing) — and adoption of tech seems to be speeding up.

Not all technology needs to be used by many people to be transformative — e.g. automated forecasting might be consulted by journalists (or AI advisors) and used in news articles, just as satellite data informs the weather forecasts we all benefit from.

In cases where widespread adoption is needed, existing platforms and AI intermediaries can significantly cut down diffusion lags. Spam filters are built directly into email systems that people already use. People might increasingly defer to AI assistants on which tools to use or systems to install (and these assistants can reduce switching costs).

And we should be careful with our intuitions about the speed of tech adoption. There’s a general pattern of technologies being viewed as far-out (almost silly) until they suddenly seem to be everywhere. (Smartphones, navigation apps, automated translation all went from extremely niche to very widespread in less than a decade.) This can happen because of network effects — if everyone is suddenly using a phone there’s more pressure to use one, too — or other social-equilibrium-curve dynamics, or the technology getting “unblocked” by reaching some reliability/cost threshold.

This is a subjective judgement! We’re not super confident in it; we just feel that the particular interventions people propose often seem underwhelming.

Of course there is a lot of AI discourse, and some that does explicitly pay attention to this (or highlight the dynamic), including e.g. the “live theory” agenda; or Buterin’s response to AI 2027.

AI-driven transformations won’t generally be discrete events; change might build pretty continuously, with different transformations often running in parallel even as they ramp up at different speeds and points in time. Still, it can be useful to imagine them represented by key thresholds, which are reached at different moments in time, and talk about their sequencing.

To give a bit more flavour on how we see the difficulty of properly anticipating technological transformation: in 1991, an optimistic case for the promise of hypertext included the following:

Overestimation of difficulties stems in part from the assumption that hypertext publishing, to succeed, must reach a large fraction of the population and contain a corpus of knowledge on the scale of a major library. These grand goals are inappropriate for a new medium (though one should seek system designs that do not preclude such achievements). This paper has argued that a hypertext publishing medium could reach the threshold for usefulness and growth with only a small community of knowledge workers, and that it could be of great value while used by only a minute fraction of the population. With this realization, the fear that hypertext publishing must be an enormous, long-term undertaking seems unmotivated. No positive arguments have been advanced to support this fear. ... It seems that the technology is in hand to develop a prototype hypertext publishing system, but how long will it take for such a medium to grow and mature to the point of practical value? If one’s measure is number of users and one’s standard of comparison is telephone, radio, television, or the (failed) goals of videotex, the answer is a long time, perhaps never. It would be hard to reach a readership as large as that of serious books, much less that of books in general, or of newspapers and magazines.

For another example of societal expectations being bad at tracking even the near future, consider that in 2020, lockdowns in many Western countries went from unthinkable to “the new normal” over just a few months.

Compeling framework on transformation sequencing. The comparitive advantage argument for working on earlier transitions is underappreciated in AI safety discourse. I've noticed similar patterns in how organizational change unfolds where initial shifts determine future option spaces more than we typically model. The epistemics-first path particulary intrigues me as precursor infrastructure.

Thanks, I found the point about sequencing both useful and thought-provoking. I am exploring all the work you and others are doing on AI for human reasoning, and this nicely articulates the potentially multiplicative impact of an epistemic shield of this kind.